In this document:

- What is biogas?

- Sustainability of biogas

- Disclaimer: It takes a community

- Biodigester design and construction

- Temperature stabilization

- Feedstock

- Storing and pressurizing biogas

- Resources

What is biogas?

Biogas is mostly methane, which is the main component of natural gas. Natural gas was produced by archae- a microorganism even older than bacteria- digesting ancient organic matter in anaerobic conditions. A biodigester replicates and speeds up this process.

Biogas does not burn quite as hot as natural gas, because it has more carbon dioxide. But it makes effective cooking fuel. In the global south, home and village scale biodigesters are becoming a popular alternative to cooking with firewood. Biogas production in tropical climates is easier than in temperate climates, because of the temperature requirements of the digester (more on that below).

Sustainability of biogas

Scale and context are critical considerations when evaluating the environmental and social value of any renewable energy source, particularly biofuels. Biofuels produced with agricultural commodities, like biodiesel and ethanol, do much more harm than good in the context of the consumer economy. By putting more stress on limited agricultural resources, they degrade the environment and increase food prices for poor people. Industrial biogas may be less directly harmful, because it uses manure and other waste products for feedstock. But it benefits and greenwashes CAFOs (factory farms) and is probably a source of leaked methane emissions.

Just like natural gas, biogas emits carbon when it is burned. However, it is considered to be carbon neutral, because carbon is pulled from the atmosphere in the process of growing the feedstock. Of course, this carbon could be sequestered in the soil if that same feedstock were to be composted. So carbon neutrality is debatable in our opinion. Also, methane leaks are a big concern.

Disclaimer: It takes a Community!

At Living Energy Farm, we spent years developing alternatives to firewood for cooking. (Solar cookers like our Roxy Oven are wonderful, but they only work when the sun shines.) Because of concerns around methane leaks, biogas was not our first choice. Instead we tried to develop technologies that would store solar heat at high temperatures. When this was not successful, we turned to biogas. It took us several years to build a biodigester, heating system, and feedstock infrastructure. We invested several thousand dollars and months of work in the project. Once established, ongoing costs are very low; however labor is still significant: about 4-6 hours per week.

While biogas is simple in concept, implementation is complex, with many problems to solve and very few turn-key solutions. This is especially true in cold climates (see section on thermal stabilization). For the most part, it is not cost-effective for a single family home or homestead to build and maintain a biodigester, except perhaps in the tropics. Much like solar thermal and green building, community is what makes this technology work.

Biodigester Design and Construction

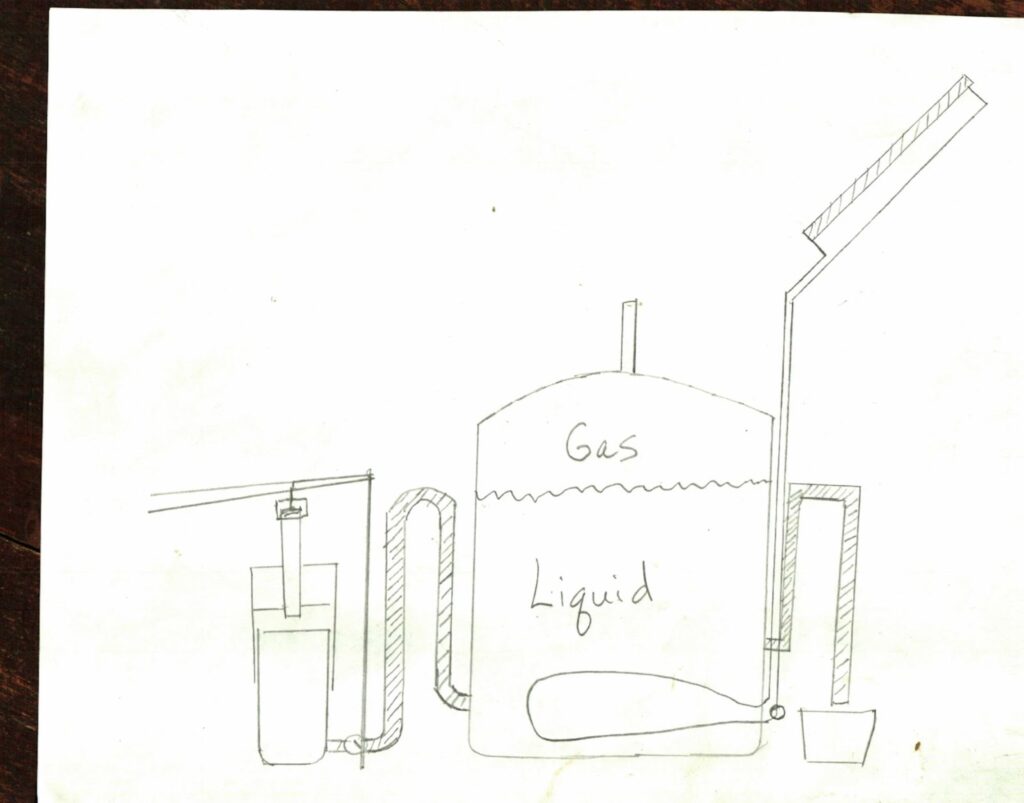

A biodigester is a plastic tank about half filled with liquid, which is a slurry of water and organic material. Our tank at LEF is 2000 gallons. Organic matter is fed into the tank, and an effluent output drains the excess liquid into some sort of holding tank. (Effluent is a valuable fertilizer. We apply it to our fruit trees.) Biogas gathers at the top of the tank, where a gas pipe exits the digester and delivers gas to burners in the kitchen.

With a small digester, feedstock may be fed by gravity. With the size of our digester, we wanted to feed with a pump and check valve, to avoid having to carry buckets of slurry up stairs every day.

Also in the graphic is a simplified representation of our solar heat loop, which provides thermal stabilization for the digester. More on that below. The heat exchanger inside the tank is stainless steel and homemade. In a temperate climate, a biodigester must have supplemental heat and must be insulated. Our digester is wrapped in two layers of strawbales, with blown cellulose over the top.

Lessons learned building our biodigester:

- Everything connected to the tank needs a flange and gasket. Most tanks of this size are low grade plastic, and there is no adhesive that will reliably stick to it. We learned this the hard way.

- Biogas contains hydrogen sulfide and is very corrosive. Everything in contact with the biogas or slurry must be plastic or stainless steel.

- Turns out that a heated digester wrapped with straw is a very attractive rodent habitat. Plumbing buried in the insulation should be PVC or copper, not pex, which is more vulnerable to rodents.

Thermal stabilization

We began our experiments with biogas by purchasing a kit from Home Biogas. The kit made some gas in late spring and summer, but shut down when the weather turned cooler, and it was very slow to come back up to production in the spring. We tried installing a solar heat loop below the tank, and covered it in fiberglass, but it wasn’t enough, the production still collapsed in wintertime.

We have come to realize that temperature control is the single most challenging aspect of maintaining a biodigester in a temperate climate. There are 3 kinds of archaea, which are active at different temperature ranges: cryophilic, mesophilic and thermophilic. Cryphilic are active at cool temperatures (under 75 degrees). They make gas, but very slowly. Biodigesters in China are typically large underground concrete tanks that are inoculated with cryophilic archaea. Gas production is slow, but the tanks are large enough to make up for this. This system works well enough, but we did not have the capacity to build such a large tank.

Thermophilic archaea are active over 110. However, they are difficult to establish and maintain compared to mesophilic. Going back and forth between mesophilic and thermophilic is also very difficult, if not impossible. For community-scale biodigesters, the recommendation is to stay within the mesophilic temperature range. Mesophilic archaea are robust and very productive. Their temperature range is 80-110 degrees, with 100 degrees being ideal. If you go over 110 degrees you will kill your culture and have to start over. Go below 80, and gas production stops.

In sunny, tropical climates, temperatures in the happy 90-100 degree range can be maintained passively, by placing a black digester in the sun. In our much cooler and cloudier climate, supplemental heat and insulation are a must. At LEF we use an active solar thermal heat loop that connects 5 flat plate collectors (115 sq ft total) to a heat exchanger inside the tank. It is very similar to our hot water system. For insulation, we have two layers of strawbales and 3’ of blown cellulose over the top.

In our hot summer months, our digester’s supplemental solar heat is enough to overheat our digester and kill the culture. We learned this the hard way. To prevent this from happening again, we installed a heat dump in parallel with the solar loop, controlled with valves, which allows us to divert heat from the digester to the heat dump when the digester gets close to overheating. Remember that you can’t “turn off” a solar loop, as the fluid will boil if it’s not circulating. Another option could be to drain the system seasonally, but we prefer the heat dump because it gives us very precise temperature control.

At LEF, it’s been a surprise to learn just how critical temperature control is to a temperate climate biogas system. It’s for this reason that we no longer recommend home-scale biogas in cooler climates. The infrastructure required to thermally stabilize a biodigester is simply not practical at the single family scale.

Feedstock

Many people think that you can’t make biogas without animal manure. This is not true, however, you do need some ruminant manure to inoculate the digester with archaea when you are starting out. We harvested 3 gallons of fresh cow manure to get our digester started, then repeated the process a few days later. It took a few weeks to make decent gas- there will be a lot of CO2 at first- but it worked.

Once our digester was making decent quality gas, we stopped adding any animal manure and switched to kitchen scraps, green grass clippings, and human waste. We purchased a “biotoilet” from Home Biogas, and plumbed the sewage line directly into the tank. (Remember that human waste must enter the tank far from the effluent output!) This setup has served us well.

Remember that feeding must be done as a slurry, mixed with water. Any vegetative matter will have to be processed somehow (chopped up) to avoid clogging the input pipe. More processed vegetative matter will also be more digestible to the archaea, particularly in an immature digester. In the summer months, most of our feedstock is green glass clippings harvested with a direct drive electric lawn mower. This is pretty ideal feedstock. If you must use hay or other mature plant material, you can either chop it mechanically- we have a silage chopper that works well for this- or do a pre-composting step before feeding. In China they use pre-composted hay, according to the Chinese Biogas Manual. We have not tried this at LEF.

In addition to the output of the toilet, we feed (on average) 2 gallons of vegetative organic matter per day. As a digester matures, it becomes more tolerant of less frequent, larger feedings.

Storing and pressurizing biogas

We started out using a 700 liter bag from Home Biogas to store and pressurize our gas. As the output of our digester improved, it became clear we would need more storage. Last year we upgraded to a bag that we purchased from Shenzhen Teenwin Environment Co., Ltd., a Chinese manufacturer. The bag is an 8’ cube with 14,500 liters of capacity.

Storage is critical because even with careful temperature control and feedstock management, biogas production is always going to be somewhat seasonal (higher in the summer months). For this reason, we “stockpile” gas in the fall, making sure our storage is full going into the winter, when we know production will slow down.

Biogas must be fed to the burner at low pressure: 2-15” of water column, which converts to 0.10-.50 PSI. A simple way to do this is to weigh down the storage bag. The Home Biogas bag has built-in pockets for sand bags. When we bought a bigger bag, we built a shed around it, and also built a floating, self-leveling platform over the bag, which we covered in sandbags. Because the top of our bag is 64 sq ft- over 700 square inches- it took quite a bit of weight to get the gas to pressure: around 200lbs in sand bags.

Resources

- A Chinese Biogas Manual is the best general source of information we have found on biogas.

- Tamera Community in Portugal also has a biodigester making gas for their community kitchen. There is some information about their design online. They do not use supplemental heat, but their climate is warmer than ours.

- The Northeast Biogas Initiative is a community collaboration for biogas education and tech development based out of Massachusetts. We have been working with them on the solar thermal/thermal stabilization piece.

- Home Biogas is an Israeli company that markets in the US. Their kits are not well suited to cold climates, but they have useful accessories like the biotoilet.

- Source for biogas storage bag: Shenzhen Teenwin Environment Co., Ltd.